aunt dorothy's funeral

I didn’t

want to look in the coffin, but from where we sat in the back pew I could see

the poof of her thin, curly gray hair peeking over the edge of the casket. Her

hairdresser had come and done it for her one last time. I can hardly imagine

the stories that hairdresser has heard from Aunt Dorothy over the years, many

of them repeats, the same ones I’d hear every December. Stories that were

making the room full of friends and family laugh just in the reminiscing of

them. Stories like the time one of her fourteen siblings was born on her

twelfth birthday, and with her hands full of toddlers she reportedly cried, “I

don’t want a baby brother for my birthday! Send him back!” That baby brother

was sitting just a few rows ahead of me now, elderly and growing more feeble

every day, but still full of the same old jokes and smiling whenever we’d laugh

and say, “Wow, good one, Grandpa.” He wasn’t smiling today though; he limped

out of the room as soon as the service was over. Aunt Mona asked if he wanted

to go see Dorothy one more time, but he said, “I know what she looks like,” and

kept moving. His brother Mickey, who I saw once every couple of years, came and

stood beside me out on the porch of the funeral chapel, and told me flusteredly

that he didn’t want to go to the cemetery, wasn’t gonna watch them put her in

the ground.

We pulled up at the Elwood Cemetery and I caught wafts of familiar memories of family reunions, drives at Christmastime, and the year we roasted a whole pig in a giant tarp in a hole dug in the ground. That was the time there were a dozen pasta salads and half a dozen jello pies and four dozen relatives that I couldn’t keep straight, so Macaela and I stuck next to Dad who seemed to be everyone’s favorite nephew and cousin and uncle. We’d sit and talk to ancient Grandpa Ernie who always scared me as a kid because of the missing fingers he’d lost in the lumber mill decades ago, and because he never smiled except occasionally when Dad made a goofy joke. And then we’d go walk through the rows of headstones, listening to Dad tell us who everyone was, but knowing we’d forget them all, so usually turning it into a game of finding the oldest birth date, which was probably something in the 1850’s. As I remember it, that was the time Aunt Mona came and laughed and told Dad that Grandma had just bought four plots in the cemetery: one for herself, for Grandpa, and for two of her kids, but apparently said, “Johnnie can get his own!” He never did; he didn’t want to get put in the ground anyway. We’d all gone and looked at the plot, just an empty piece of ground covered in mostly dry brown grass, sober for a moment considering the future names and stones that would be placed here, but hearing Grandma’s wobbly screech echo across the cemetery for us all to get back over here for a family picture. Now I looked at her name on that headstone, two dates underneath it and a bouquet of faux flowers Aunt Mona had brought up on Mother’s Day. Grandpa’s name was beside hers on the stone with one date, and I heard him behind me telling someone about how his name was right there but that he ain’t dead yet.

We pulled up at the Elwood Cemetery and I caught wafts of familiar memories of family reunions, drives at Christmastime, and the year we roasted a whole pig in a giant tarp in a hole dug in the ground. That was the time there were a dozen pasta salads and half a dozen jello pies and four dozen relatives that I couldn’t keep straight, so Macaela and I stuck next to Dad who seemed to be everyone’s favorite nephew and cousin and uncle. We’d sit and talk to ancient Grandpa Ernie who always scared me as a kid because of the missing fingers he’d lost in the lumber mill decades ago, and because he never smiled except occasionally when Dad made a goofy joke. And then we’d go walk through the rows of headstones, listening to Dad tell us who everyone was, but knowing we’d forget them all, so usually turning it into a game of finding the oldest birth date, which was probably something in the 1850’s. As I remember it, that was the time Aunt Mona came and laughed and told Dad that Grandma had just bought four plots in the cemetery: one for herself, for Grandpa, and for two of her kids, but apparently said, “Johnnie can get his own!” He never did; he didn’t want to get put in the ground anyway. We’d all gone and looked at the plot, just an empty piece of ground covered in mostly dry brown grass, sober for a moment considering the future names and stones that would be placed here, but hearing Grandma’s wobbly screech echo across the cemetery for us all to get back over here for a family picture. Now I looked at her name on that headstone, two dates underneath it and a bouquet of faux flowers Aunt Mona had brought up on Mother’s Day. Grandpa’s name was beside hers on the stone with one date, and I heard him behind me telling someone about how his name was right there but that he ain’t dead yet.

Someone escorted Grandpa and Uncle Mickey to a single row of plush green chairs that were set right in front of the pink coffin for the closest of family. The two of them put their heads together and talked, probably about something totally unrelated, finding solace in the presence of the other. The rest of their siblings were back in their hometown in Johnson City, Tennessee - the ones who hadn’t already passed. Only Grandpa and Uncle Mickey had followed Aunt Dorothy when she migrated to Oregon decades ago. She was the reason they came, and after all those many, many years, they were about to say goodbye. They would have rather been anywhere else, but they were here because of her. And I was too, quite literally; it was her pioneering to Oregon that brought Grandpa to the place he met Grandma. How crazy that I owed this tiny, feisty old lady my very existence.

Aunt Dorothy was one of those relatives who never really knew anything about me, but loved me because I was her flesh and blood and would always assume I was in the mood for cookies. We went to her house every December to cut down a Christmas tree that we’d find in her fields. After freezing on the extended tree hunt that generally ended back at the very first tree we’d seen, we’d pile into her tiny kitchen that smelled like her tiny, ferocious dogs and she’d make us cups of apple cider straight from the powder packets and talk to Mom and Dad about relatives I’d lost track of, that Mom and Dad might have lost track of too. I’d pass the time timidly scratching the dogs, or looking at the dozens of painted porcelain plates mounted on the walls, or finding my photo on the crowded refrigerator door, or staring at the family picture of Aunt Dorothy’s kids and grandkids and great-grandkids who never got older because I only saw them in this same picture every year, all in denim and red. Those people were standing all around me now, grown up and holding kids of their own, gathering around the coffin covered in the dahlias she had so loved.

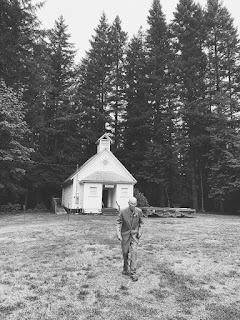

We were a motley crew, a conglomeration of people somehow related to these redneck Tennessee transplants, or kids who grew up nearby calling her “Aunt Dorothy” whether she was actually their aunt or not. We had nothing in common except these ancestors of ours, and that we could join together and pray the Lord’s Prayer in the traditional King James Version in a tiny, mountain cemetery. Soon the funeral officiants were helping Grandpa stand up and guiding him to place his pink rose boutonniere on the coffin before walking away. He turned immediately to the nearest person and started telling them about his stroke, anything to change the subject. I asked if he wanted one of Aunt Dorothy’s dahlias and he told me to pick one out for him, so I placed a big, burgundy bloom in his suit jacket pocket and started slowly leading him to the one-room schoolhouse where lunch was being served.

We were a motley crew, a conglomeration of people somehow related to these redneck Tennessee transplants, or kids who grew up nearby calling her “Aunt Dorothy” whether she was actually their aunt or not. We had nothing in common except these ancestors of ours, and that we could join together and pray the Lord’s Prayer in the traditional King James Version in a tiny, mountain cemetery. Soon the funeral officiants were helping Grandpa stand up and guiding him to place his pink rose boutonniere on the coffin before walking away. He turned immediately to the nearest person and started telling them about his stroke, anything to change the subject. I asked if he wanted one of Aunt Dorothy’s dahlias and he told me to pick one out for him, so I placed a big, burgundy bloom in his suit jacket pocket and started slowly leading him to the one-room schoolhouse where lunch was being served.

And that was all. Family and friends slowly migrated from the grave to the schoolhouse, dahlias in hand. This is how life is supposed to end, I thought. Celebrated, but simple. Surrounded, but peaceful. Sorrowful, but communal, moving seamlessly into the next moment and then the next, until the gathering is ours and the flowers are in our memory and we join the fellowship of the saints before us, saints that I can hardly imagine without those old, repeated stories and the poofy gray hair.

That was a wonderful narrative. Thank you for sharing. Marsha

ReplyDelete